While fiction in (English) translation can appear fairly invisible at times, there are books which are genuinely well known throughout the Anglosphere, not all of them coming from nineteenth-century Russia. One such novel is Albert Camus’ work L’Étranger (variously known as The Outsider or The Stranger), which has become as much a part of pop culture overseas as in France, so when a writer decides to take the book as the starting point for his own novel, you can be sure of one thing – there’s bound to be a lot of interest.

While fiction in (English) translation can appear fairly invisible at times, there are books which are genuinely well known throughout the Anglosphere, not all of them coming from nineteenth-century Russia. One such novel is Albert Camus’ work L’Étranger (variously known as The Outsider or The Stranger), which has become as much a part of pop culture overseas as in France, so when a writer decides to take the book as the starting point for his own novel, you can be sure of one thing – there’s bound to be a lot of interest.

Whether it’s any good in its own right is another matter entirely…

*****

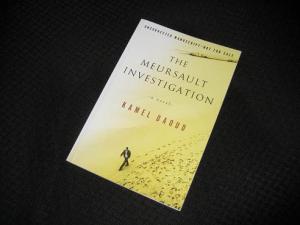

Kamel Daoud’s The Meursault Investigation (translated by John Cullen, review copy courtesy of Other Press) is set in a bar in the Algerian coastal city of Oran, where an elderly Arab man is chatting to a stranger about the past. This is no ordinary conversation, though, mainly because our friend Harun is no ordinary man. Seventy years earlier, on a blisteringly hot day on an Algiers beach, his brother was gunned down by a Frenchman. His name? Meursault – you might have heard of him…

The anti-hero of Camus’ novel is shown in a new light here as Harun explains to the visitor, and the reader, how Meursault’s account of affairs, published after his release from prison, has become so widely known. However, despite the Frenchman’s in-depth discussion of his life and crime, there’s something that seems to have been forgotten. Meursault’s victim has disappeared, whitewashed from the pages of the novel and from history, a nameless victim of the writer’s philosophical struggles. And that’s why now, in the dark, dingy Oran bar, Harun has decided it’s time to tell the other side of the story.

By all accounts, The Meursault Investigation is an important book. It’s been sweeping up prizes in France, and it would be surprising to see it ignored in next year’s IFFP and BTBA prize season too. If you’re a fan of Camus’ work, this is required reading, a new take on an old story, one which examines our beliefs and shows us that every tale has at least two sides. By re-examining the evidence, we might find that our opinions (and our sympathies) change somewhat – history is never static.

While the content engages with L’Étranger , in terms of style it’s another book which instantly comes to mind. The set-up is very similar to that of La Chute (The Fall), another of Camus’ novels (in fact, the contre-enquête of the French title brings to mind the juge-pénitent of The Fall…), and here there’s also a visitor to a café, a voluble, friendly voice – our friend Harun certainly likes to talk:

“Ha, ha! I’ve always wondered, what’s the reason for this complicated relationship with wine? Why is it treated as though it’s of the devil, when it’s supposed to be flowing profusely in paradise? Why is it forbidden down here and promised up there? Drunken driving. Maybe God doesn’t want humanity to drink while it’s driving the universe to its place, holding on to the steering wheel of heaven… Yes, yes, I agree, the argument’s a bit muddled. As you’re starting to realize, I like to ramble.”

p.43 (Other Press, 2015)

This is probably a good place to praise the excellent work done by Cullen, as the success of the voice is an important part of the novel. Harun is a mesmerising presence, and I could feel how the original would have sounded without the need to back-translate, the speaker’s vibrancy coming through in the new language.

Once we think about content, however, it’s all about Camus’ more famous work, with Daoud’s novel a critical look at Meursault’s account of the story. Harun’s life has been dominated by the event, his brother’s murder overshadowing his own existence – yet:

“He’s the second most important character in the book, but he has no name, no face, no words. Does that make any sense to you, educated man that you are? The story’s absurd! It’s a blatant lie!” (p.43)

As the story progresses, we see that Harun’s anger has less to do with the murder itself than with the way in which his brother, Musa, has been erased from history, his only remaining trace an anonymous corpse on the beach, one which swiftly vanishes forever.

One of the focuses of the ‘investigation’ is on examining Meursault’s ‘testimony’ and correcting it. Early on, Harun informs us that he has no sister, and that the woman who provoked the incident was probably a prostitute. It’s a minor detail, but it’s to prove the thin end of the wedge, with Harun (and Daoud) using the doubt this event inspires to examine other ‘facts’ of the story, even questioning Meursault’s presence at his mother’s funeral. We only have Meursault’s word as to what happened, and if one detail is wrong, how can we be sure that the rest is true?

On a deeper level, though, The Meursault Investigation is about challenging the oppressor’s version of events. When Harun questions the validity of Meursault’s story, he’s actually asking whether the voice of the colonialists can be trusted – in their own language:

“Therefore I’m going to do what was done in this country after independence: I’m going to take the stones from the old houses the colonists left behind, remove them one by one, and build my own house, my own language. The murderer’s words and expressions are my unclaimed goods.” (pp.1/2)

While Harun wants to introduce the reader to Musa, giving his brother a presence denied him by Meursault, he’s also acting on behalf of his community. L’Étranger is the voice of the French in Algeria, les pieds-noirs, but Daoud’s book gives the natives a voice, acting as a post-colonial rewriting, or correction, of history, using the oppressors’ language to strike back.

Part of the fascination of the book for the casual reader are the parallels found between the two stories, starting from the very first line, in which we learn “Mama’s still alive today”. Anyone who has read Camus’ novel will see allusions all over the place, with Harun’s mother living in Marengo (where Meursault’s mother died) and Harun himself spending time in prison and arguing with an imam. Even the plot structure is similar, with its fateful twist half-way through.

In fact, Harun is a counterpart of sorts to Meursault, his life echoing the past. He has his own demons to face, his own suspicion of organised religion, his arrest and jail time mirroring Meursault’s own (down to the question he’s asked in prison…). Like Meursault, he’s persecuted not for what he has done but what he hasn’t done; while Meursault is condemned for the lack of grief shown after his mother’s death, Harun’s absent enthusiasm for the cause of independence almost costs him his life. There’s also a mirroring of the voices, Harun’s warm, passionate plea for life contrasted with Meursault’s cold, nihilistic tone of the grave.

The ties between the two books are unmistakable and inextricable, and the blurb from French magazine Le Monde des Livres (“In the future, The Stranger and The Meursault Investigation will be read side by side.”) sums up most people’s thoughts. It’s probably a fair assessment (it’s certainly what I did), and it’s impossible not to compare the two. But is that a good thing?

There’s a fine line between homage and fan-fiction, and while The Meursault Investigation is a long way from Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, it can tread that line rather precariously. At times, there’s an uneasy conflict between pop references to a classic novel and Daoud’s attempt to create a lasting work of his own. Yes, it’s entertaining, but is it really The Meursault Investigation or merely L’Étranger redux? On occasion, I found myself simply looking for references to Camus’ work, feeling smug when I found them – but does that make it a successful piece of literature in its own right? Like the shadowy ‘ghost’ in Harun’s bar, Meursault is constantly in the background, a presence which threatens to overshadow Daoud’s work.

Having said that, early reviews of the book, including that of Michiko Kakutani in The New York Times, have been very positive, so I may be alone in my doubts (and I’m not saying I didn’t like the book – I enjoyed it greatly). Perhaps over time, after the inevitable reread, I’ll come to appreciate it more. One thing’s for sure – while I’m not convinced that it’s up there with the book that inspired it, The Meursault Investigation is definitely a work which will provoke a lot of discussion. And in a society where fiction in translation is mostly starved of oxygen, that can’t be a bad thing 🙂

I think I’m looking forward to reading it because of the links to Camus – definitely some fanfictioning aspect of me there. Good enough to stand on its own two feet? Well, we’ll see…

LikeLike

Marina Sofia – The further I get away from it, the more I’m coming around to it. The main reason for my doubts was my loathing of people piggybacking on other writers’ creations. Having said that, I wrote 1400 words on the book, so it must have something 😉

LikeLike

Certainly sounds interesting!

LikeLike

Paul – Definitely interesting, not a book which should bore people 🙂

LikeLike

I thought this was brilliant …I read it in French when it was first published . I didn’t see it as fan fiction at all ….certainly it’s an homage ..and I loved those echoes you refer to …but I thought it was a very clever way of re-telling the story of modern Algeria. The voice of Harun was compelling . I thought Daoud pulled off an incredible feat ….a tribute to Camus as well as confronting history and the present day .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Helen – I’m not quite as sold on it as you obviously are 😉 A good read, yes, but you run the risk of being overshadowed when you mess with a famous text, and I’m not convinced that Daoud’s got away with it completely…

LikeLike

I like premise of this Tony it’s due out next month here from another publisher in uk .There has been a lot about camus last fee years his notebooks were all publisher in France the other year so a fresh look at his work through another writers eyes seems interesting

LikeLike

Stu – It’s a great idea; I’ll be interested to see what you make of it 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t believe it – due for publication on 2 July, I ordered my copy of this yesterday!!! My thoughts will be a few months coming one would think, given my “to be read” pile. Was attempting to get a little ahead of the IFFP longlist for 2016, thinking this would be high on judges lists. Thanks for the review.

LikeLike

Tony – No worries 🙂 Already out in the States, so you could have got in even earlier 😉

LikeLike

Excellent review Tony.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Emma – Thanks 🙂 Another commenter above loved it after reading it in French, so perhaps it has that certain je ne sais quoi that the translation hasn’t managed to bring across…

LikeLike

I commented a bit on a paragraph between the French and English versions in my billet.

LikeLike

Emma – Yes, I saw that – I do wonder if I’d like it more in French…

LikeLike