As you’re all no doubt aware, I’m always on the look-out for interesting Japanese literature, and one recent venture that has certainly caught my eye is the collaboration between Stone Bridge Press and Monkey: New Writing from Japan, namely their joint Monkey imprint. I’ve already enjoyed Hiromi Itō’s The Thorn Puller (translated by Jeffrey Angles) and Hiromi Kawakami’s Dragon Palace (translated by Ted Goossen), and perhaps to prove that they can publish books by people not called Hiromi, a third title in the series recently appeared. It’s another slightly unusual work, but very enjoyable all the same, and for anyone who likes vicarious literary journeys, this may well be a book for you.

As you’re all no doubt aware, I’m always on the look-out for interesting Japanese literature, and one recent venture that has certainly caught my eye is the collaboration between Stone Bridge Press and Monkey: New Writing from Japan, namely their joint Monkey imprint. I’ve already enjoyed Hiromi Itō’s The Thorn Puller (translated by Jeffrey Angles) and Hiromi Kawakami’s Dragon Palace (translated by Ted Goossen), and perhaps to prove that they can publish books by people not called Hiromi, a third title in the series recently appeared. It’s another slightly unusual work, but very enjoyable all the same, and for anyone who likes vicarious literary journeys, this may well be a book for you.

*****

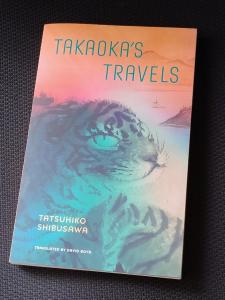

Takaoka’s Travels (translated by David Boyd, review copy courtesy of the publisher) introduces us to the titular prince, a real-life ninth-century royal who took the tonsure at an early age after some political issues. We join him in Guangzhou, where, in the company of two monks, Anten and Engaku, he’s about to set sail for Hindustan, fulfilling a lifelong dream to visit the homeland of Buddhism. With a last-minute addition to the party (Akimaru, an escaped slave the group smuggles on board the ship), it’s time to head off, with everyone looking forward to reaching their goal.

Alas, it’s not quite as simple as that – this is a journey that rarely proceeds smoothly. Fate continually intervenes, pushing and pulling the prince and his entourage all over south-east Asia, leading to encounters with interesting people and fantastic beasts, all of which the prince takes in his stride. While this is all well and good, he’s not getting any younger – eventually he starts to wonder whether he’ll ever make it to his destination.

Takaoka’s Travels is a joy from start to finish as we bounce from adventure to adventure, the tales getting taller by the minute:

Just then, as they dug, a bell jangled behind them, and an odd-looking figure appeared. Completely naked, he had the body of a man and stood on two legs as people do, but his hairy head was that of a dog. He had pointy ears and long whiskers on his muzzle. Was he human or not? The four travelers were staring at this dog-headed man in utter astonishment when he opened his mouth to speak:

“What do you think you’re doing, digging up those bamboo shoots?”

To their surprise, the dog-headed man’s Tang speech was impeccable.

p.86 (Stone Bridge Press, 2024)

Assailed by ghostly pirates, led to a harem of Kalaviṅkas, sleeping in the company of dream-eating creatures and searching for bodies in a flying canoe, Takaoka rarely has a dull moment. Divided into seven chapters, Shibusawa’s novel takes us and his characters on a wonderful trip, where it’s most definitely all about the journey, not the destination.

Given the magical nature of the book, it won’t come as a surprise that there’s also a major focus on dreams. The prince is a dreamer, in more ways than one, and from his youth he has had a tendency to encounter people and creatures while asleep. On more than one occasion, it proves hard to distinguish dreams from reality, especially when events seem to bleed from one to the other.

There’s a Buddhist taste to affairs, but that’s not to say that dry religion dominates proceedings as there’s plenty of focus on the erotic, too. The importance of his father’s lover, Kusuko, in the prince’s life is clear throughout, and in the form of Akimaru we have a gender-bending element to the tale. Then, of course, there are the customs and the culture of the lands our hero passes through:

As he walked on, he saw drawings of what appeared to be female genitalia, suggesting that this path had been traveled by people throughout the ages. As with the lingam in Chenla, these graphic depictions failed to shock the Prince in any way. (p.105)

No, Prince Takaoka isn’t a man to let a little pornography get him off balance…

Shibusawa’s novel comprises a mixture of styles. It’s most often a sort of documentary, including plenty of authorial intrusion, and we’re treated to a fair bit of history, too, with the narrator filling us in on interesting facts about the places we’re visiting. We’re never able to get too complacent, though, needing to be on our guard:

“Miko, you know nothing! That’s why you can say such foolish things. At risk of anachronism, let me explain. The great anteater will be discovered roughly six hundred years from now when Columbus arrives in what will then be called the New World. So how can we be staring at one here and now? Can’t you see its very existence defies the laws of time and space? Think about it, Miko!” (p.30)

At which point, the anachronistic giant anteater pipes up to defend itself!

Boyd’s brief translator’s afterword introduces us to the real Prince Takaoka and Shibusawa himself, and both are fascinating characters, albeit in very different ways. In addition to penning his own fiction, Shibusawa was a translator of the work of the Marquis de Sade, which inevitably led to an obscenity trial:

…Shibusawa – having deliberately trimmed away the more soporific passages in Juliette – was accused of taking Sade’s work into his own hands and making the obscene work even more obscene in translation. (p.186)

Hmm – a serious accusation. So how did the writer approach it?.

…Shibusawa strolled into court wearing sunglasses and smoking a pipe – if, that is, he bothered showing up at all. He used his time in the national spotlight to ridicule his accusers, which quickly won him the admiration of the literary world as well as the general public.

You’ve got to admire his style – a shame this was his only novel…

Kevin Brockmeier’s back-cover blurb claims that “Takaoka’s Travels will somehow remind you, simultaneously and impossibly, of a hundred books you’ve loved and nothing you’ve ever read”, and there are certainly hints of many classics of world literature here. Gulliver’s Travels is an obvious influence, and with the Buddhist undertones, the Chinese classic Journey to the West also immediately springs to mind (even if we have no Monkey Demi-Gods along for the ride…).

A slightly less obvious influence, though, might be Voltaire’s Candide, the story of a young man roaming the world in search of his fortunes, and his lost love. Like that book, Takaoka’s Travels sees our hero repeatedly taking one step forward and two steps back, constantly thwarted by fate in his attempt to finally see Hindustan. Another parallel can be found in his companions, with both Takaoka and Candide accompanied by a pessimist and an optimist, even if Pangloss’ belief that “tout est pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles” is perhaps not one that Takaoka, as a Buddhist, would subscribe to!

In truth, though, there’s no real need to play literary detective and look for connections – Takaoka’s Travels is a book that can stand on its own merits. An enjoyable romp through semi-history and fantasy, it introduces us to a man willing to experience all the world has to offer in the short time remaining to him on this Earth. Takakoka is someone to admire (as is his creator), and this is a book to enjoy, time and time again.